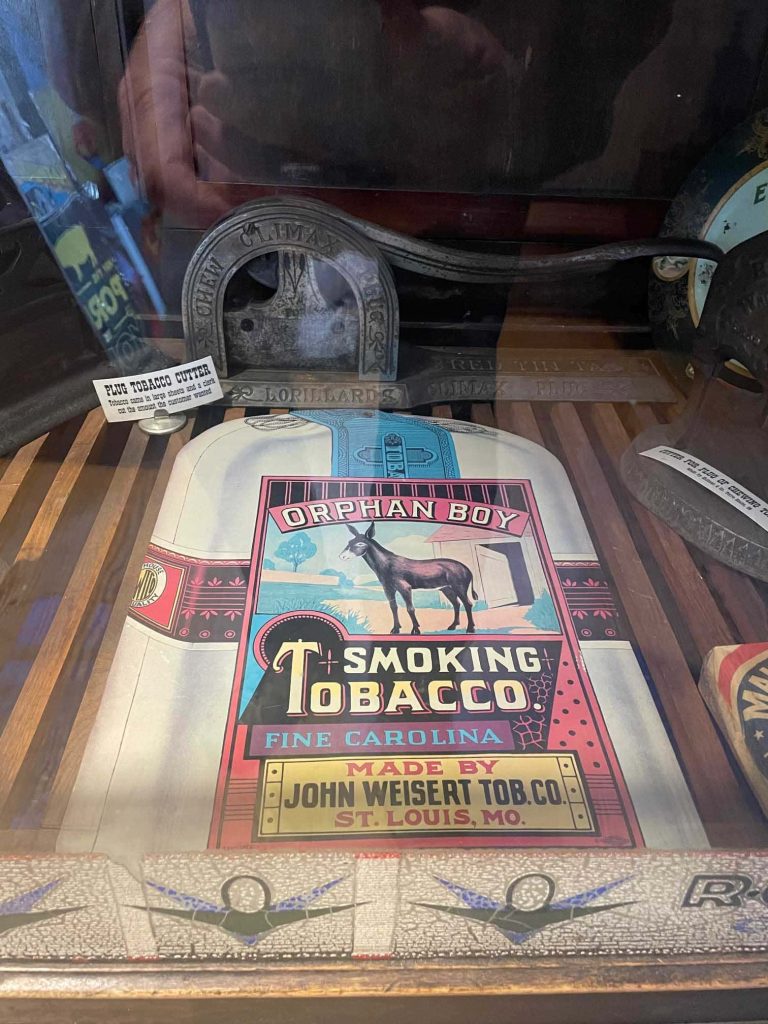

The stunningly beautiful pre-Civil War era cabinets in the main Museum room are the first thing most visitors notice when they enter. They form a perfect backdrop for all the rest of our artifacts and exhibits. There are literally thousands of individual artifacts in the Museum thoughtfully assembled to convey the look and feel of an authentic 19th century drugstore. Most of the artifacts fall into categories or groups of similar objects related to each other. Example categories include Apothecary Jars, Tools of Pharmacy, Vintage Advertising, and Patent Medicines. We also have interesting displays about Soda Fountains, Candy and Gum. Many of the items prominently featured and promoted in old drugstores are thought of very differently today. Tobacco products are a good example. At the same time, there are many examples of old treatments in our collection that mirror modern concerns. Treatments for hair loss, cough and cold, chronic fatigue, depression, and anxiety are just as sought after today as they were over 100 years ago. To learn more about some of our collections, check out the topics below.

The cabinets in the main Museum room were made in Cincinnati, Ohio, and originally installed in the Sam Hoshour Drugstore, in Cambridge City, Indiana, in 1852. They are of exceptional quality, handmade of walnut and ash wood, and in outstanding original condition for their age. Large glass panels are inset at the top of each cabinet. Each glass panel is expertly hand painted, with many featuring advertising for products of the day on the reverse (back) side of the glass. This method of “reverse glass” painting of the advertising panels allowed the glass to be easily cleaned without harming the painted areas. The base front counters are elaborately decorated with combinations of Italianate style brackets, carvings of fruit, and decorative applied moldings. The countertops themselves are even assembled in a striking pattern of alternating strips of light ash and dark walnut. The advertising painted on the glass panels was added over a period of years during the first decades the drugstore was in business. Itinerant (traveling) sign painters were hired by national companies to paint ads promoting their products in selected stores. The store owner was likely paid directly or received products or discounts as compensation for allowing the advertising. The exact years these signs were painted was never recorded, however, we do know one sign had to be painted between 1865 and 1867, because the business it advertises was only under that name, for those three years.

In the early days of drugstores, pharmacists made many of their own pills, lotions, salves, elixirs and more according to individual medicine “recipes” each Doctor ordered for their patient. Prescription medicines were so varied, it was not possible to make large quantities of specific medicines and doses in factories. Manufacturers focused primarily on supplying bulk chemicals and ingredients, so each pharmacist could then make the individual prescription medicines and doses ordered by the Doctor. This meant early Pharmacists had to manufacture many of the medicines they dispensed and needed quite a few tools. Pill rollers, pill tiles, suppository molds, mortars and pestles, herb cutters, precision scales, and many other tools were needed. The Museum has examples of these and more. Our docents are happy to demonstrate how these tools work and invite visitors to give them a try!

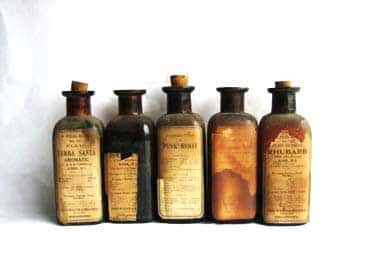

Apothecary style glass bottles with content labels protected under glass covers (commonly called “Label Under Glass” are one of the most recognized and numerous items in any historic drugstore. They came in an extremely varied number of sizes and styles and were used for both liquids and powders. These attractive bottles, many with fancy decorated labels usually have their contents described in Latin. They traditionally lined the shelves on the side of the drugstore and were used to store the raw materials Pharmacists combined (compounded) to make prescriptions ordered by the Doctor. These bottles were prominently displayed, in part to impress customers with all the material on hand, as well as to show Pharmacists had a great deal of knowledge to deal with so many different ingredients. The Bottles were not only used to store materials for medicines. Pharmacists of the 19th and early 20th century also dispensed a huge variety of non-medical products mixed from his stock bottles. These products included but were certainly not limited to poisons for vermin infestations, insecticides, paints, perfumes, spices, flavoring agents, glues, and more. Bulk materials were not only contained in bottles. The Museum has many examples of ceramic jars, and even some wooden cylinders. Bulk dried and processed herbs and plants used in medicines were commonly stored in tin containers.

The word “Medicine” is an extremely broad term, one that can apply to many different types of products taken with the intention to heal, or prevent illness. Some of these products are ones available only when a Doctor prescribes it, others can simply be purchased without any prescription, or even mixed up from common ingredients found at home. The Hook’s Drugstore Museum has literally thousands of examples of products that have been referred to over the years as “Medicines”. Below are some interesting examples of the “Medicines” found in the Museum.

Generally any medicine that can only be sold to a customer based on a Doctor’s written order is referred to as a “Prescription” Medicine. Originally, because of extremely varied training and experience, each Doctor developed unique “recipes” to mix the medicines they recommended to best treat their patients illness and disease. We can think of it today as similar to cooking. Many cooks bake cakes, but over time develop “secret” ingredients, or special processes that they believe make their cakes better than other cooks. So it was in a time when medicine was more “art” than “science”. Doctors communicated their special medicinal “recipes” to Pharmacists by written prescription, which specified the ingredients used to make the medicine, as well as the dose and frequency for that individual patient. Pharmacists would then have to laboriously hand-mix and make the medicine for the patient, following the Doctor’s prescription. This process to provide prescription medicines was obviously very time-consuming, and vulnerable to error given the training and experience of both the Doctor, and the Pharmacist, availability and quality of the ingredients at the pharmacy, on and on.

Beginning in the second half of the 19th century, enterprising companies were beginning to realize the vast potential of offering factory made versions of medicines frequently prescribed by physicians that were ready to dispense, as opposed to the pharmacist having to laboriously make each prescription medicine by hand. Many of these companies had previously focused on simply selling bulk materials to Pharmacists. Pharmacists and the manufacturers soon realized large factories could be far more efficient, cost effective, and consistent in dose and ingredients than making everything by hand. As prescription medicines and their preparation became more and more complex over time, the idea of pharmacists making different individual medicines and dosages for each Doctor became impractical and declined dramatically. Today, Pharmacists who custom mix special prescriptions individually are known as “Compounding Pharmacists”. The Museum features several displays of early standardized manufactured medicines. Examples of medicines from Abbott, Merck, Squibb, Parke Davis, and especially Eli Lilly (founded in 1876 in Indianapolis) are found in the Museum. Manufactured medicines intended to be dispensed only by prescription are also called “Ethical” pharmaceuticals. This is to clearly differentiate prescription medicines from those that can be sold directly to customers without a prescription, commonly called “Over the Counter” or “OTC” medicines.

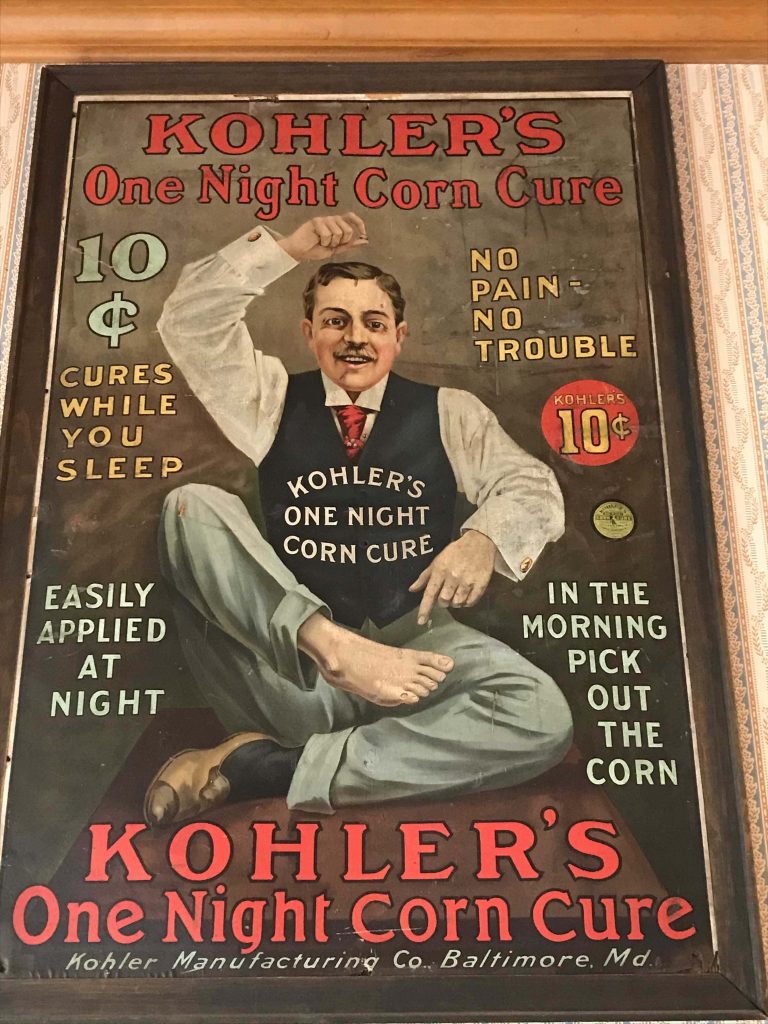

Medicines not requiring prescriptions may or may not have been recommended by Doctors, however customers could simply purchase these ready-made products directly off the shelf, or “Over the Counter ”, a very convenient and frequently less expensive alternative to prescriptions. Companies who made these products created demand through colorful and attractive labels and images on the packaging, similar to the way wines, and many other direct to consumer products are still marketed today.

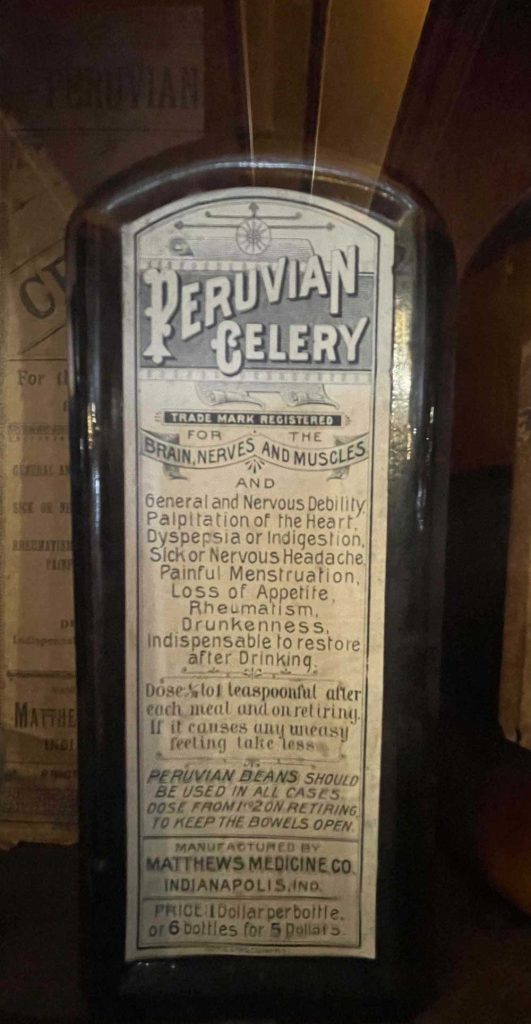

A problem came as the less scrupulous of these non-prescription medicine companies also made unsubstantiated and sometimes outlandish claims of all of the wonderful things their medicine could do. They relied on a trusting and poorly informed public who frequently distrusted or could not afford a Doctor, or for disease and illness which medical science had no treatment for. Many dishonest companies made large profits selling their products of false hope, sometimes because they were addictive due to the narcotic and alcohol content. They were able to afford expensive and splashy advertising, which further convinced people of their value, without having to consult a Doctor.

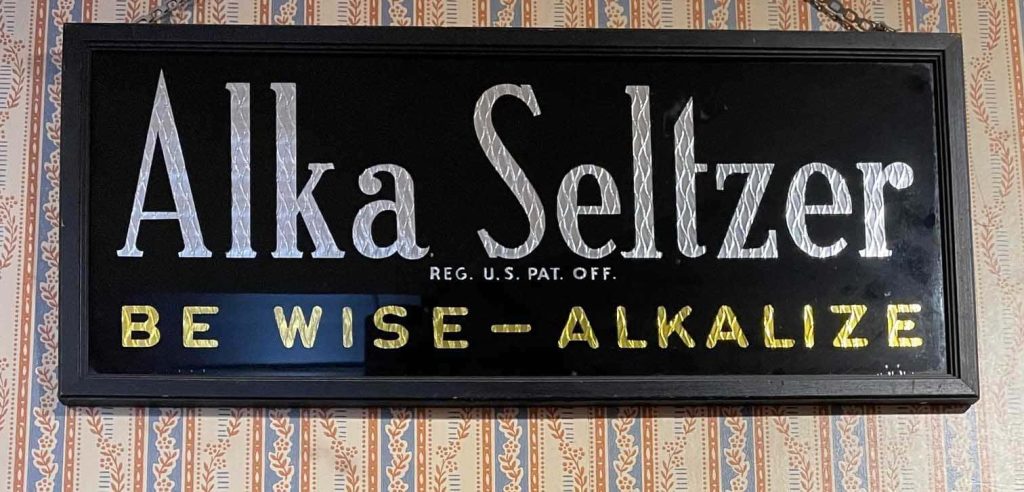

There were, and still are, a large number of effective medicines that do not require a prescription to treat simple problems (think cough, cold, upset stomach, etc.). These common treatments were and still are well known, and endorsed by medical professionals.

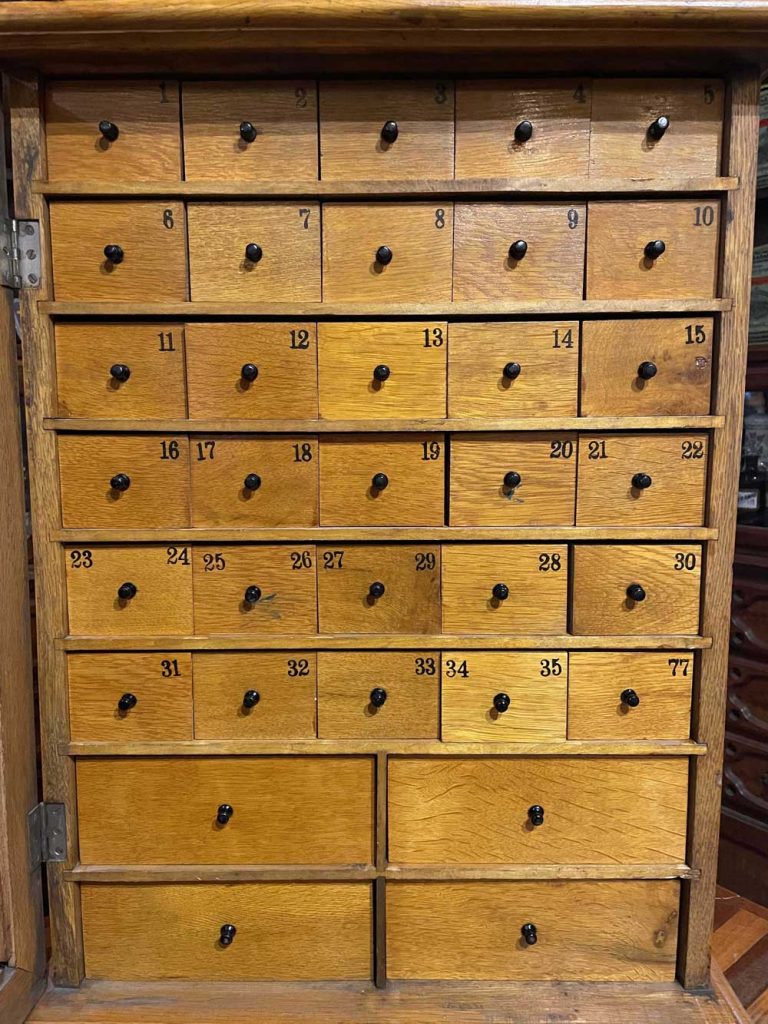

These non-prescription medicines frequently touted the theory that most illnesses were actually the result of the body simply being “out of balance” from its normal state, and Homeopathic Therapy could safely and effectively restore this natural balance without causing harm. These treatments were usually associated with being less toxic than many Patent medicines, but were largely ineffective, similar to a placebo. Hook’s has one such Homeopathic example prominently displayed, a countertop cabinet featuring “Humprey’s Medicine. Humphrey neatly categorized and organized the illnesses and diseases their medicines could treat by a numbering system, outlined in advertising and signs. To treat your illness, all you had to do was identify the number assigned to your problem, find the associated numbered drawer in the display cabinet, and then purchase that particularly numbered medicine from the numbered drawer. Suspiciously, all the Humphrey medicines, regardless of the number illness or disease they were intended to treat, look the same. They are all exactly the same color, and size, small round white pills.

So called “Patent” Medicines became wildly profitable and prolific during the late 1800’s, however many were later found to secretly contain dangerous narcotics or alcohol to encourage repeat use. The term “Patent” Medicine originated in England, and referred to the fact that at one time, medicine makers there were able to obtain an exclusive government “Patent” for claims of what their “Medicine” could allegedly treat, or “cure”. No evidence of effectiveness or safety was necessary to obtain such a patent, the applicant simply had to be the first one to file and successfully obtain the legal Patent”. As you might imagine, this system encouraged all kinds of unscrupulous businesses to invent and patent incredible claims of what their medicine could treat, and then effectively bar all other businesses from making a similar claim. It had no basis of whether or not the medicine actually worked or was even dangerous.

Explore some of the interesting medicines of the past in the Hook’s Collection in the images and descriptions below.

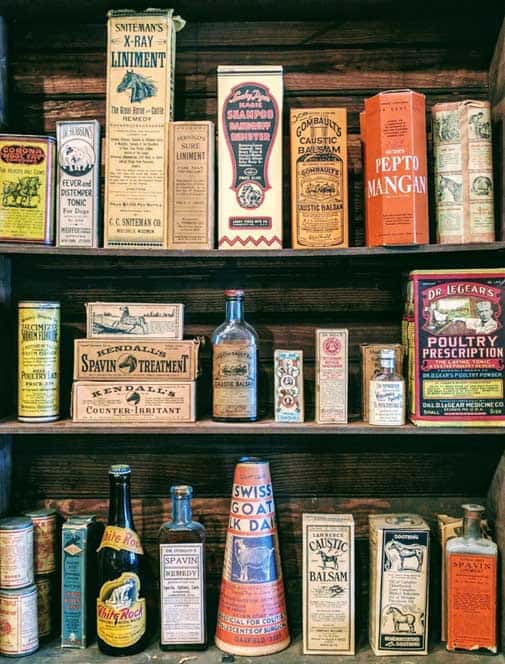

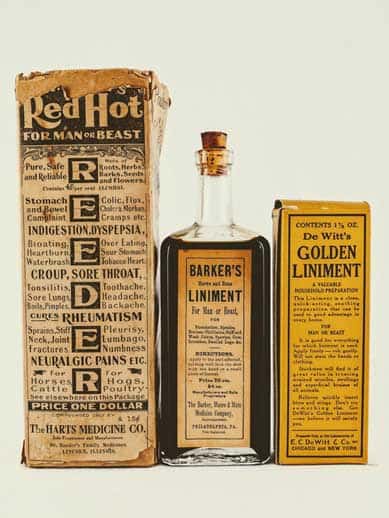

These were sold in a variety of colorful eye-catching containers, frequently with images that helped identify the intended “patient”. Similar to human medicines, “Remedy” and “Cure” are seen in some of the descriptions. Some product names hinted they were at the forefront of the newest medical advances, for example the Sniteman’s “X-Ray” Liniment on the top row. The “Perigo’s Sure Liniment” on the top row claims: “For Man Or Beast”. This was a very practical, since it increased potential users to include both humans and animals, and, played on people’s popular belief that many external medications (like liniments) could be good for both people and animals.

A variety of colorful labels and images helped to promote historic products from the Hook’s Collection associated with hair care. These examples show that people in the past had the same concerns about hair as we do today. Some of the products are concerned with purely cosmetic issues like hair color and creating interesting “hair-do’s’ ‘, while others addressed complaints like dandruff, itching scalp, and hair loss. “Youth Craft for Hair and Scalp” primarily claims relief from dandruff and itching, but the name (Youth Craft) implies additional benefits, including “stops hair loss”, as well as the wording “in many cases, has restored gray hair to its natural color”. Parisian Sage, the last bottle on the right offers no specific benefit except a general claim it is a “Hair Tonic” and “Scalp Treatment”, leading the consumer to simply imagine the many potential benefits, based on the image of a healthy young girl with long flowing locks, and a name, “Parisian”, that hints at exotic and expensive European origins.

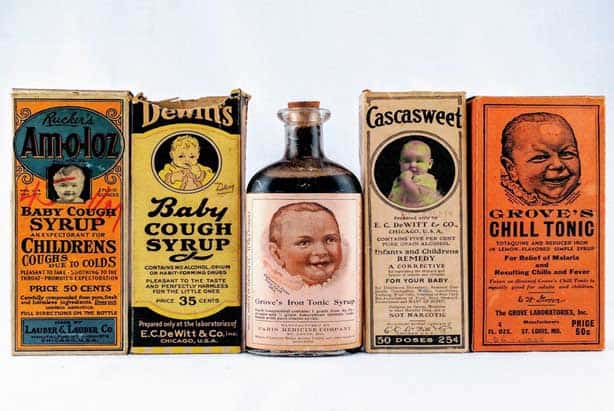

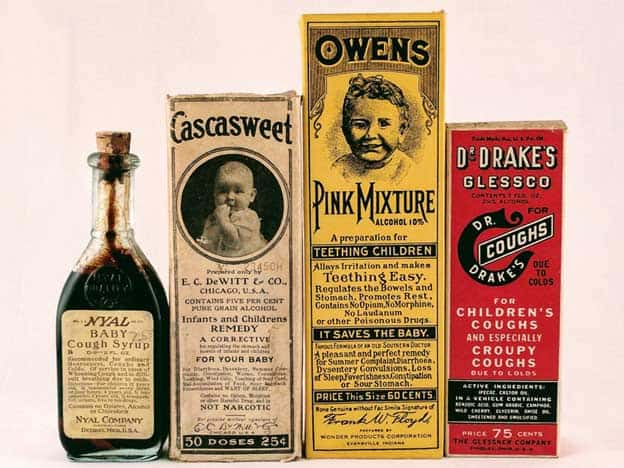

Medicines to treat children and babies are frequently found in the Hook’s collection. These products and their advertising invariably show aspirational images of healthy and happy children to convince consumers of their value and efficacy. These examples from the early part of the 20th Century include treatments for common cough and colds (Am-o-loz, and Dewitt’s), constipation (Cascasweet), and a general health tonic based on iron supplement (Grove’s Iron Tonic Syrup). Note that Am-o-Loz indicates no narcotics or harmful substances, and Dwitt’s claims no opium, alcohol, or habit forming drugs. This wording is a necessary reassurance to customers of that day who may have had experienced older, dangerous products for children, frequently laced with powerful narcotics and sedatives, sometimes with lethal results. The last box, Grove’s Chill Tonic, reminds us of a time when a disease like Malaria, now a distant faded memory in the U.S., was a serious concern for health.

Customers looking for relief from aches and pains a hundred years ago made liniments a common medicine at local drugstores. It was a crowded market for these types of preparations, with literally hundreds of companies trying to sell products. Each company tried to broaden their appeal to increase sales. A common practice was to advertise it could be used on animals as well as humans. The term printed on the boxes was commonly, “For Man or Beast”. Although the practice seems foreign and strange today, there was a popular wisdom that horses and other work animals benefited from the same liniments that helped humans, and vice – versa. The Harts Medicine Company took a further measure to try and and make their product (Red Hots) more saleable. In addition to aches and pains, they further claimed benefit for a broad array of unrelated ailments, including stomach and bowel complaints, colic, cholera, indigestion, dyspepsia, joint and neck fractures, sore throat, croup, on and on.

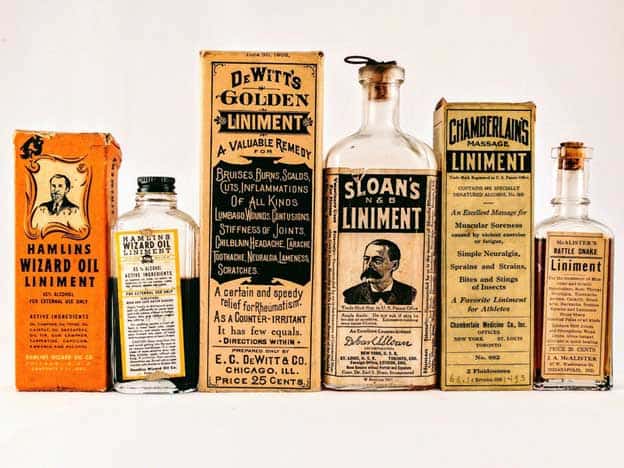

Common ailments like aches and pains bring forth a large number of treatments. Literally hundreds of entrepreneurs produced a myriad of different medicines. Many of the medicines of this time identified themselves as the “invention” or the “discovery” of a particular charismatic individual, frequently a Doctor, but not always. People with very little education, or insufficient background to understand science, were more likely to place their trust, and hence their money, in products that were promoted by, and named for people. Hence, as with the examples of these common liniments, each has a makers name,and not uncommonly an image to go with the name, and sometimes, even that individual’s personal signature, all in an effort to build familiarity and trust with potential customers.

Today we understand that pain is of course not a disease in and of itself, but rather a symptom. In an age however where not infrequently there may not have been any reliable way to either diagnose, or treat the actual problem, decreasing pain was very important to quality of life. An interesting feature of two of the medicines above, “Nature’s Oil Pain Destroyer” and W. P Calebler’s “Uze-It Pain Oil” is that they were promoted as useful for both internal, and external pain. They could simply be rubbed on as a liniment for joint or muscular pain, or taken internally for stomach pain, cramps, and even toothaches. Only the Loxol “Pain Expeller’ is listed as external use only. Importantly, the Loxol product ingredients includes capsicum, which is basically hot pepper spice, and still commonly used today in medicines to help relieve a variety of pains. The ingredients of the “Nature’s Oil Pain Destroyer”, and the “Uze-IT Pain Oil” are not listed, so we are left to guess about how they might have, or might have not been effective.

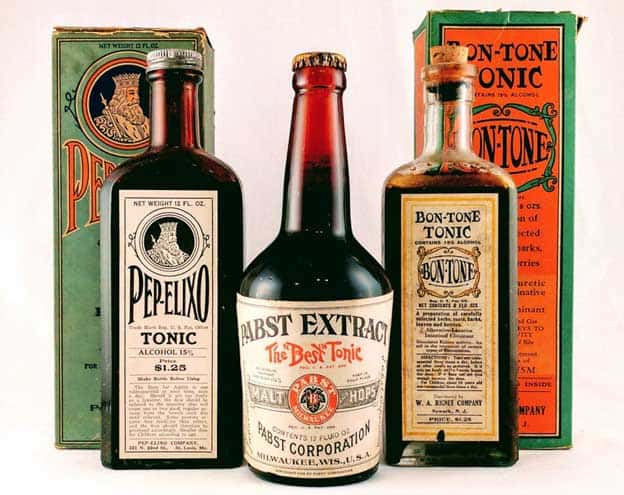

Tonics were very popular “Medicinals” for many years. These products promised a variety of benefits for users, well beyond just a generalized “pick-me-up”. Primary claims for the “Pep-Elixo” and Bon-Tone” tonics included laxative properties, but Bon-Tone also mentioned things like kidney stimulant and rheumatism. The most interesting however is the Pabst Extract “The Best Tonic” . Yes, this is the same company famous for “Pabst’s Blue Ribbon” beer. Pabst started selling their malt extract as a health benefit and tonic as early as the 19th Century. In contrast to other tonics, Pabst targeted benefits for nursing mothers as their market. This interesting sideline product took center stage at the company however, soon after Prohibition started in 1920. Along with cheese making in their beer cellars, and a line of soft drinks, these products became the main line, and literally saved the company from closure until prohibition legislation was finally lifted. The label on this bottle is 1926, clearly during the prohibition period.

Some of the more interesting historic medicines in the Hook’s collection are those targeted to the specific “ailments” of women. Popular belief held that women had certain inherent weaknesses and “infirmities” specific to their gender that responded to medication. These products claimed to address a broad variety of problems, many associated in one way or another to women’s reproductive capabilities. The probability of any product helping such a broad range of illnesses encompassing infections, hormonal imbalances, pain, and surgical problems is clearly seen today as impossible.

In a time when many women suffered illnesses that had no well understood treatment, or cause however, people wanted to believe that these so-called “medicines” could bring relief. The most outrageous of these examples is Dr Geo Lenniger’s “For-mal-de-hyde”. It is unknown if this product actually contained formaldehyde, or simply tried to capitalize on a common chemical name that consumers might recognize. Formaldehyde the chemical is probably best known for its past use as an embalming fluid. Today it’s still in widespread use in manufacturing, but recognized as highly toxic for human exposure, even in very small quantities. We certainly hope that this product falsely advertised its association with this highly dangerous compound.

These bottles contain examples of a class of old Medicinals called “Bitters”. Historically, “Bitters” was simply an alcoholic preparation, flavored with botanicals, such that it tasted sour, or bittersweet. From that simple basic formula, makers of patent and other types of “medicines” created a nearly endless variety of products with an even larger list of promised benefits. Many people reportedly treated bitters as an alternative alcoholic beverage, they were in fact sold in similar size containers to spirit liquors It was more socially acceptable in some circles to “Take your Bitters” rather than drink ordinary spirits. The aqua blue hand-painted bottle in the center is one of the oldest medicine bottles in the Hook’s collection, and originally read “Clifford’s Indian Vegetable Bitters”. Thought to date to about 1850, this hand-blown and laboriously hand painted and decorated bottle must have been very expensive in its day.

Safer medications for children. After the initial passage of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906, makers of all products labeled as medicines had to disclose their ingredients. Many people discovered for the first time that many popular children’s medicines for teething, cough, and colic contained dangerous amounts of narcotics. No exact numbers can ever be known, but it is now widely acknowledged that these products with morphine, laudanum, and other highly addictive and dangerous substances killed thousands of children as they slept. The public quickly demanded safer non-narcotic medicines for children, and many companies responded, clearly labeling their products as non-narcotic and safe. Interesting to note however that Owen’s Pink Mixture was 10% alcohol, and Cascasweet was 5% alcohol.

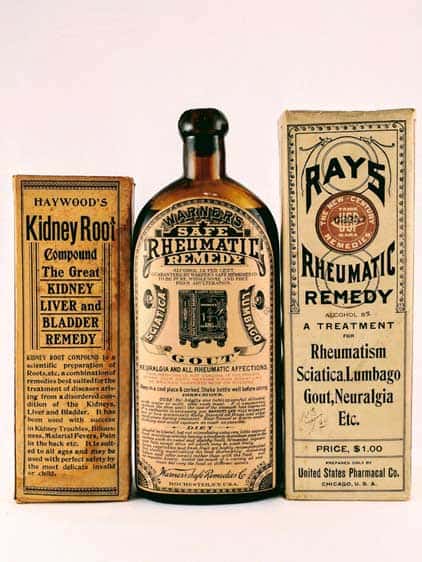

Many “Patent Medicines” were marketed as both safe and effective in a large number of often unrelated diseases and illnesses. There was no requirement for companies prior to the beginning of Drug Regulations that began appearing in 1906 to provide any proof that their medicines actually had any benefit, were safe, or even what all the ingredients were. Makers of “Remedies” tended to make their claims for chronic illnesses with symptoms that varied over time from better to worse, and back to better again. This variation in symptoms over time led many patients to believe these products were helpful. The word “Remedy” was taken to imply it helped, but did not cure, which was easier for people to believe. Many of these “Remedies” were originally branded and marketed as “Cures”, however over time, as Drug Regulations began to crack down on outrageous claims, they moved to calling themselves “Remedy” rather than “Cure”.

The history of Hook’s Drug Store, while fascinating, stands on the shoulders of those pharmacists that came before John Hook. This museum is a tribute to those early scientists and pharmacologists that discovered and invented the remedies that fill the shelves of this amazing store. Without the hundreds and even thousands of years of early experimentation by early humankind around the globe, our drug store shelves, and our health care would look vastly different today.

You may not be aware, or even have heard the term, but these early scientists were deeply rooted (pun intended) in the study of pharmacognosy. What is pharmacognosy? Loosely translated, pharmacognosy is concerned with the study of medicinal drugs that come from plants or other natural sources.

Look carefully at the shelves of Hook’s Drug’s Store and you will see that the magic of pharmacognosy is all around you. Below are just a few examples of the pharmacognosy in our museum. We invite you to visit us and see pharmacognosy for yourself.

Rhubarb root as seen here was commonplace in a late 19th century pharmacy. It has been used in medicine for over 2,000 years, originating in China and Tibet. A 19th century pharmacist may have recommended a dose as a cathartic, meaning to treat constipation.

A very common ingredient for many uses including itchy skin and muscular pain camphor is derived from the leaves of an evergreen tree called Cinnamonium camphora. As seen in this photo, camphor was the primary ingredient in Hamlins Wizard Oil Liniment. Other natural products derived from plant sources used in this topical product are thyme oil, cajeput oil, sassafras, and turpentine.

Back in the day, plantago seeds were ground up and used for many indications. The topical product below claims to be effective for toothache pain. Today, a relative of plantago called psyllium seed is commonly used orally as a bulk laxative.

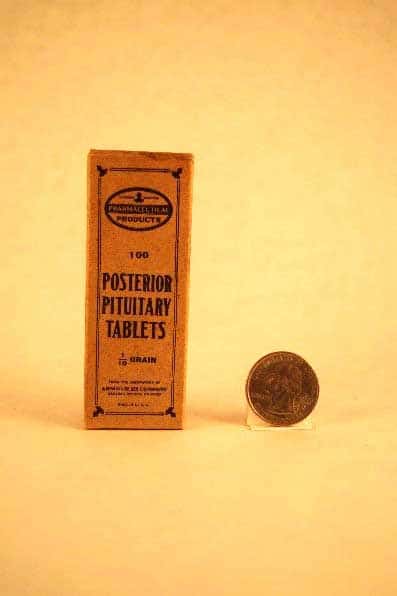

Products derived from animal sources for human consumption were sometimes sold in old time pharmacies like Hook’s. Pancreas, pituitary, and thymus tablets can still be found in health food stores making statements that have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration.

Did you know the soft drink industry emerged from drugstores, and that most major brands of soda we enjoy today were originally intended for medicinal purposes and invented by pharmacists? The Hook’s Soda Fountain has been operating for over 50 years and serves thousands of ice cream sodas and phosphates at each Fair. Nostalgic gums and candies also have a long association with drugstores and are an important part of our guest experience.